Biophysics of chromatin organisation

Every eukaryotic cell faces the challenge of organizing its genome into the nucleus: a compartment that is orders of magnitude smaller than the length of the DNA itself. While solving this topological organization problem, this process also needs to be precisely regulated, as the genome needs to control the accessibility of the information it encodes.

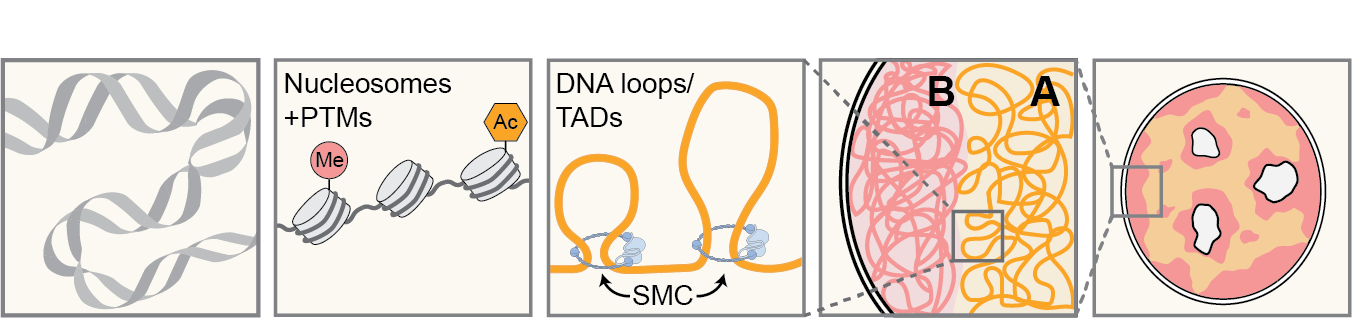

Nuclear organization occurs on several levels, all involving physical processes. First, the basic folding of the genome, coated with modifiable histones, is dictated by principles of polymer physics. Second, active systems driven by molecular motors, such as SMC (Structural Maintenance of Chromosomes) proteins, result in chromatin loops. Third, the nucleus is roughly divided into compartments that preferentially associate with chromatin of similar transcriptional status (“A” representing active euchromatin, “B” is silenced heterochromatin).

Our lab aims to examine the functional relevance of the genome architecture and the biophysical mechanisms that drive it. We use a multifaceted and interdisciplinary approach, ranging from single-molecule biophysics to genomics and engineering.

Measuring across scales

Our interdisciplinary research combines techniques from physics, cell biology, and biochemistry. Our aim is a holistic approach of chromatin biophysics across scales.

On the smallest scale, we use single-molecule force spectroscopy to examine mechanical properties of DNA. We tether DNA between beads, which we can trap and manipulate using optical tweezers. We can monitor the force response of the DNA and its modifications by manipulating the beads. The combination with confocal microscopy allows visualization of factors that bind to the DNA. We are interested in monitoring binding kinetics of diverse chromatin interactors including transcription factors, chromatin remodelers, and respressing proteins.

On the mesoscale, proteins and nucleic acids form complexes and compartments in the nucleus. As many essential nuclear processes including transcription, silencing, and repair, require assembly of many factors, these biomolecular condensates can help concentrate and organize the execution of these processes. We are interested in understanding how the material properties of these condensates relate to function.

On the scale of a whole nucleus, we are interested in understanding how chromatin relates to the stiffness of the cell and the nucleus. Cells are continuously exposed to forces in their native environment. How they deform and adapt upon experiencing these forces is essential for survival. Chromatin takes up a significant portion of the nuclear volume, and is thus a major structural component. In our lab, we monitor and quantify the response of cells and nuclei upon experiencing force.